"Iraene" asks the following question on the Antiwork subreddit.

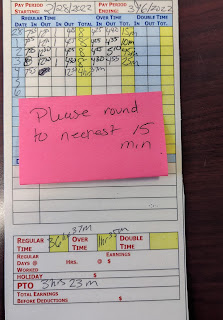

I was told to round down or round up my time. So if I start work at 7:55 I need to put 8. If I work 37 minutes, I should round down to 30, instead of 45 because this is a common business practice. Is this normal? I have entered exact times on the card and into ADP so idk why it's a problem now.

While this practice as explained appears to be legal, it doesn't necessarily mean it's a good idea for the employer, at least according to this employment lawyer.

Let me explain.

The Fair Labor Standards Act (our federal wage and hour law) requires that an employer pay an employee at least a minimum wage for all time worked. Employers must track the time non-exempt employees spend working. Many use a swipe-card system, biometric scanner, computer log-in and -out, or even an old-fashioned punch clock for this purpose. Under the FLSA's regulations, the use of time clocks or other similar recording system is not required.

The problem with time clocks is that they permit early punches. An employee might punch in at 6:55 am for a shift that starts at 7 am. Is that extra five minutes "on the clock" considered "working time" that must be paid? Well, it depends. Is the employee actually engaging in work (which must be paid), or is the employee punching for convenience and waiting around to work (which can be unpaid)? As the FLSA's time clock regulations make clear, "[E]mployees who voluntarily come in before their regular starting time or remain after their closing time, do not have to be paid for such periods provided, of course, that they do not engage in any work. Their early or late clock punching may be disregarded."

Of course, those added "on the clock" minutes could lead to confusion as to whether they should have been paid, which, in turn, could lead to expensive FLSA collective action lawsuits. Thus, the FLSA also permits time clock rounding. The FLSA's regulations permit an employer to round employee punches to the nearest 5-, 10-, or 15-minute interval, as long as it is a true rounding and works to the benefit of both the employer and the employee. As the Department of Labor states, "For enforcement purposes, this practice of computing working time will be accepted, provided that it is used in such a manner that it will not result, over a period of time, in failure to compensate the employees properly for all the time they have actually worked."

This, however, begs the question, when does a rounding system result over a period of time in a failure to compensate employees for all hours worked? Again, it depends. As long as rounding works both ways (up and down from the midpoint of the chosen rounding unit(, an employer should be okay. But that doesn't mean an employer is all clear. Per the DOL, employers should discourage "major discrepancies" between "clock records and actual hours worked," as they could "raise a doubt as to the accuracy of the records of the hours actually worked." In other words, frequent and repeated rounding could call into question the accuracy of an employer's overall time records.

So that's an employer to do? Here are three suggestions.

1/ Consider a shorter rounding period. A 1/10 of an hour (6-minute) rounding period permits for much greater synergy between the time on the clock and the time actually spent working than does a 1/4 hour (15-minute) rounding increment.

2/ Prohibit employees from clocking in before a certain time and out after a certain time. All actual and bona fide working time must still be paid, but a two- or three-minute buffer around the start and ending time limits time spent on the clock while not actually doing anything work-related (such as grabbing a cup of coffee or having a smoke).

3/ Simply pay to the punch. Yes, this encourages abuses and would allow employees to punch early or late to try to "game the system" to earn extra pay. But those abuses are serious performance issues that should be handled as such with discipline and, if repeated, termination.

Regardless of the choice you make (rounding, punch limits, pay to the punch, or something else), no employer should ever run payroll without someone (such as a supervisor) putting eyes on all employees' punch or other time records to ensure accuracy. Further, employees should understand via policy their obligation to bring incorrect paychecks to your attention as soon as possible after being paid. Working time is still working time, but at least you'll have these extra checks and balances in place to push back on claims of inaccuracy and underpayment.